I made pork sausages the other night, with lentils and a crisp celery salad. I don’t usually make sausages, especially pork sausages, but I saw a recipe by Molly Baz for sausages, mustardy puy lentils and a celery salad and decided to follow it.

The recipe called for puy lentils, I used black (is there a difference?) and cooked them till they were toothsome. They were then tossed in jammy onions, just cooked garlic and two heaping tablespoons of Dijon mustard (I took liberties here, I eat mustard by the spoonful) and tossed with a splash of water to make a saucy situation that I could eat just as is. I’ve cooked this since, and mixed it with white basmati rice, roasted broccoli and tuna. I will cook it again, soon, and eat it with a fried egg and heaps of parsley.

I’d never actually cooked pork sausages before, something I realised as I was cooking them. It’s difficult to know when they’re cooked, because they get blackened and charred so quickly. I was tempted to pull them off the heat when the pan started to smoke, but I added a knob of butter, because that’s what Rebecca May Johnson did and it seemed like a good idea. It was. They were sweet and juicy, with the char offering a balancing bitterness. I’d forgotten that pork is sweet, and instead of acting like the main element in this dish, I feel like it was more of a secondary ingredient, a seasoning even.

I grew up with meals that were presented as ‘meat + something else’ and I’m trying to move away from this hierarchy now that I’m in control of the menu in my own house. We eat meat maybe once a week, sometimes more, but I don’t like it being the centre of the meal, as if all the other ingredients are dependent on it.

As a meat eater in a pathologically meat-eating country, I am really trying to eat less meat, even when I’m eating meat.

When we eat steak, we almost always serve it with tomatoes dressed in some variation of toasted fennel, anchovy and vinegar; roasted broccoli and, if it’s a Sunday, smashed potatoes. When I think of this meal, I don’t just think of the steak, but how the fennel/anchovy/tomato liquor mixes with the steak juices to make the most perfect dipping sauce for the smashed potato. I think of how when Rob cooks the steak (his job, he’s better at it than me) he always cooks it on a cast iron skillet so that it gets a rich, caramelised crust and how when this is covered in juicy, dripping fresh tomatoes, it reminds me of summer and eating outside in our apartment block’s garden in a way no other dish really can.

Writing this makes me realise that what I love about this dish isn’t really the steak, but actually the tomatoes.

We don’t eat celery enough, was what Rob said about the salad. He’s right, we don’t. I found the celery leaves a bit rough and grating. My palate felt itchy after I finished and perhaps this is because of the freshness of the celery? I think I’ll swap out the celery leaves for something like radicchio next time. I’ll keep the celery though, nothing matches that crunch.

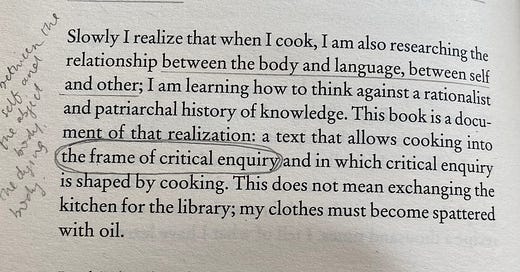

I cooked pork sausages because Rebecca May Johnson writes about cooking sausages in Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen (2022). In the chapter, “Consider the Sausage!” she endeavours to make Mrs Beeton’s sausages from a 19th century edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. Her (now fallen) hero, D.W. Winnicott, “describes cooking from a recipe as the antithesis of creativity” (118). RMJ disagrees, so she makes herself the cook to test his theory of creative living. She wants to see whether she will, in fact, “get nothing from the experience except an increase in the feeling of dependence on authority” (121).

(I am now wondering if D.W Winnicott was not also contributing to the gendered portrayal of a woman in the kitchen as obedient, passive and submissive. As if he was offering a reason, a justification, for her obedience and ‘dependence on authority’ with the recipe as the culprit? RMJ notes the gendered nature of his binary description of the ‘creative’ cook vs. the ‘obedient’ cook and now I wonder if this binary has not assisted in setting up the preconception of male ‘chefs’ and female ‘cooks’.)

What Winnicott does with his declaration of recipes being the opposite to play, is silence the cook and the “hungry bodies”(120) they cook for. He says they don’t matter, that people would much rather live with a ‘creative cook’ that makes a mess and burns food than with someone who mindlessly follows a recipe. To Winnicott, a cook who follows a recipe is rote, obedient, ‘slavish’ and compliant. He sets up a binary: Good cooks shoot from the hip! With no consideration for those who might have to eat their food. Bad cooks just follow recipes and end up with something boring, yet still useful because the food is edible, tasty even.

As a recipe follower, I disagree with this (so does RMJ). I find space in recipes. I find space within the form that emerges, a feeling that brings me immense comfort. When I cook, I feel like I’m changing the shape of a recipe to suit my own “difficult body”. Molly Baz suggested two teaspoons of dijon in her lentils. I said ‘No, I want two tablespoons’ because these lentils are for my body and my unnaturally high tolerance for mustard and vinegar. I find rebellion.

According to RMJ, “every time a recipe text is performed there is a refusal”, that “the partial erasure of a recipe through a disobedient performance can signal the tentative emergence of the cook’s voice” (109). When my my mom tells me stories of her childhood, she often mentions how they only ever ate the food my Gran liked. She didn’t like pumpkin, broccoli or cabbage, vegetables in general really. She also didn’t like any baked custard deserts. So, my Gran didn’t cook these foods for her family. People might think this was a selfish decision, especially when thinking of cooking for a family of young children. But my Gran, cooking in the 1960s and 70s, didn’t like certain foods, so she left them out of the recipe all together, for everyone. She was the cook and that was her refusal. I like to think that my Gran found some agency in this rebellion. I think she did.

I also think it was also an encouragement to her children to maybe try and develop their own palates by trying new foods on their own, but I don’t know if this worked.

Concerning the sausage recipe, RMJ looks to it as a palliative:

to relieve me from a feeling of abstraction that arose from tying myself in knots writing. It is like a mist descends, I felt distant from the world, bodies, things.

Reading the recipe for pork sausages and lentils; mentally gathering the ingredients I have and don’t have; putting on my apron; rinsing lentils until the water runs clean, bringing them to a boil; chopping garlic, onions (not in the recipe but I like them) and celery; frying the sausages (panicking because I think they’re burning), realising they won’t look like the picture; heaping mustard into the cooked lentils, adding water and raw garlic; tossing the celery with some leaves, salt, vinegar; tasting everything and feeling real again and purposeful. I look to the sausages to bring me back to a place of words, of generation.

I know I can’t get to this place by myself. So, I look to a set of rules laid down by someone else. Cooking means having a conversation, or an argument, with those who’ve cooked before. This generational, often critical, discourse brings me back to the ‘world, bodies, things’. By adding to this conversation, I can bring something to life. A feeling maybe or even a person and a memory.

My mom has a few handwritten recipe books from my Gran, with recipes she developed and collected throughout her life. She’s continued this practice herself, my mom, with recipes I can mostly remember from childhood and school bake sales. I’ve often been puzzled by this, because my mom doesn’t like cooking or baking, or she at least likes telling people that she doesn’t like either of these practices. Taking the time to recall and research recipes from her life, and from ours, has never seemed like something she would like doing. But then I think of my Gran’s recipe for cucumber mousse. A recipe almost everyone in my family, close and extended, can’t stand because it’s made of grated cucumber, mayonnaise and green gage jelly. This is then all mixed together until it looks something like radioactive pig slop, put into a bundt mould and refrigerated until set. My mom only ever made this recipe for my Gran at Christmas time (her and my uncle were the only family members who ever ate it, sometimes my Oupa too). Despite knowing this recipe by heart, come Christmastime my mom would still take my Gran’s recipe book down from the shelf and diligently follow her instructions to the letter.

My Gran died this year, at 96. I haven’t found myself thinking about her so much; her voice, her smell, what she’d say to me on weekends when they came to visit us on the farm, her clothes. But more of her food, or rather the food she liked to eat. Like this cucumber mousse that was awful but made her happy when she saw it on the Christmas table.

I think my mom writes recipes down, so that she can bring the people who gave them to her back to life. I know when my Oupa dies, I’ll just want to eat roast chicken for every meal, followed by Aylesbury vanilla ice cream to try and keep him with me for as long as possible. Lucky for us (and my stomach), he’s still here.

Maybe this Christmas, we’ll make my Gran’s cucumber mousse again and place it at the centre of the table, like a shrine.

"I find rebellion." I love that line. I often think of comic books and how going back to the 9-panel layout is often the best way to rebel against form, to really test the medium's boundaries, instead of throwing formal structure to the wind in favour of two-page Marvel-esque spreads.

It's the small rebellions we find that matter.

I grew up in a home where we didn't eat spinach or olives or pork (and probably a number of other things) because my mother didn't eat them. I found the exclusion humorous and never minded. But before now I'd never considered the rebellious nature behind that stance. "She was the cook and that was her refusal. I like to think that my Gran found some agency in this rebellion."

I know what my mum and I will be talking about when I call her again. Thank you for the conversation, Robyn.

Robyn, surely you are too young to know what green gage jelly is! LOL Does that even exist anymore? I feel that maybe even I am too young to know... (although sadly I def do recall it). What an apocalyptically bad flavour choice that was... what was wrong with lime or green apple?

When we were kids my mom used to make an equally terrifying and wobbly concoction of whipped, aerated evaporated milk folded into that same green jelly and we actually did call it Toxic Sludge! It was one of those appallingly bad desserts that you can't help but eat - sucking the set foamy goodness through your teeth to liquefy it. Food memories, even the bad ones, are still great though, aren't they?

As always I thoroughly enjoyed reading Chomp Robyn and I look eagerly forward to the next instalment.

PS. I love a good pork banger.